Freudian Psychology

The Psychiatrist Who Gave His Patients Malaria

Julius Wagner-Jauregg and his relationship with Sigmund Freud.

Posted March 23, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Though Julius Wagner-Jauregg and Sigmund Freud had similar backgrounds and were friends for decades, their lives took very different paths.

- Wagner-Jauregg advocated controversial treatments for shell-shocked soldiers in WWI, and Freud was called on to review his practices.

- Wagner-Jauregg successfully treated neurosyphilis patients, up to half of all psychiatric inpatients, by infecting them with malaria.

- Though he created the first effective treatment for a devastating illness, later unfortunate political associations clouded his memory.

Sigmund Freud and Julius Wagner-Jauregg were arguably the two most well-known physicians treating mental illness in their time. Their lives had many similarities: They were born and died within about a year of each other, went to medical school and post-graduate work together, and tried to go into internal medicine but went on to treat psychiatric illness. Freud, of course, founded the psychoanalytic movement, while Wagner-Jauregg was the first psychiatrist to win the Nobel Prize based on his malaria treatment for the psychotic state produced by neurosyphilis.

The two interacted throughout their careers and had a decades-long friendship, which came apart only in old age when their lives took very different courses: Freud was harassed by the Gestapo and died in exile in London, while Wagner-Jauregg became a prominent Nazi supporter. In this two-part blog, we will explore their curious longstanding relationship.

This post lays the groundwork by reviewing the life of Wagner-Jauregg, which is less familiar. In the second part, we will see how he and Freud interacted and explore their similarities and differences.

Julius Wagner, born on March 7, 1857, to a prominent family in Wels, Upper Austria, was the son of Adolf Johann Wagner, a civil servant with a background in jurisprudence and politics. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was 10. Later the father was reassigned, and they settled in Vienna in 1872. Upon retirement, the father was made a nobleman and acquired the hyphenated family name of Wagner-Jauregg.

He entered the prestigious University of Vienna in 1874. His father was said to have favored him going into philosophy, which took fewer years of training, but he also recognized that medicine might be natural, recalling that he had a history of dissecting dead animals. Julius ultimately chose medicine, and during his student years, he took some of the same courses as Sigmund Freud; the two became acquainted and began their long relationship.

Wagner-Jauregg graduated in 1880 and began an assistantship in a pathology institute, where he and Freud worked together. He had become interested in internal medicine, but in 1882 his applications were turned down, as were those of Freud. Uncertain about what to do next, Wagner-Jauregg was considering moving to Egypt when two professor acquaintances he saw at a coffeehouse mentioned an open assistantship at the Vienna’s Asylum of Lower Austria clinic. Though Wagner-Jauregg had had virtually no training in psychiatry, he applied the next day and, to his surprise, was accepted. Armed with a hastily purchased textbook of psychiatry, he began his training. By 1887 he was qualified in psychiatry and neurology and managed the clinic.

During this period Wagner-Jauregg became interested in dementia paralytica, a delayed consequence of syphilis that was responsible for from 20 to 50 percent of psychiatric hospitalizations and which was almost invariably fatal.1 He observed that some patients seemed to get better after contracting illnesses such as erysipelas and typhoid fever and thought this might be related to the fever they produced.

By 1887, he began to speculate whether purposely infecting patients with febrile illnesses such as erysipelas and malaria might benefit mental illnesses. His preliminary studies with streptococci from erysipelas patients met with little success. He later tried tuberculin, which was discontinued when it became apparent that the regimen had significant, sometimes lethal, side effects.

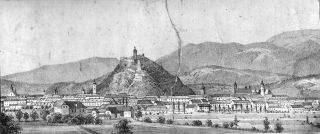

In 1889 Wagner-Jauregg moved to the University of Graz in southeastern Austria (see illustration).

As it happened, this area was known for its high rate of cretinism and goiter. While trekking in the nearby mountains, he saw many of these individuals, and in 1892 began studying them. By the late 1890s, it became clear that these disorders were associated with thyroid malfunction due to inadequate dietary iodine, and he led an effort to require adding iodine to salt. The years in Graz were also significant in his personal life, as in 1890, he married Balbine Frumkin, a Jewish woman from whom he later was separated; after her death, he re-married in 1899.

In 1893 Wagner-Jauregg returned to Vienna as director of the university’s asylum-based clinic and then one at the General Hospital. Later, during World War I, his work moved in a new direction. Many of his patients were soldiers with head injuries or shell shock. He became a leading proponent of using drugs with unpleasant side effects and an aggressive form of electrical therapy, seemingly punitive and designed to return soldiers to the front quickly. Knowledge about this method became widespread and reports that it was not very effective led to public resistance. In 1920 he was indicted for employing treatments that could be construed as torture. Among those who were called to testify was Sigmund Freud. Ultimately he was acquitted, and remarkably, the two remained friends.

Wagner-Jauregg’s opportunity to resume febrile therapy also came along during World War I. In June 1917, he encountered a soldier who contracted malaria in Macedonia. He obtained blood samples and injected them into two patients with dementia paralytica; he then took blood from them and gave it to additional patients. All were later treated with quinine for their malaria. However, his initial reports of success were tempered in 1918 when he stumbled upon a particularly potent strain of malaria, which he had apparently not carefully checked, and several patients died. By 1920, he had obtained a somewhat safer strain, and ultimately the treatment was so beneficial that he won the Nobel Prize in 1927.

After retiring in 1928, Wagner-Jauregg remained active. He speculated about using chemically-induced fevers and applying malaria therapy to schizophrenia and mood disorders. In doing so, one could see a progression from the man who in 1890 had ceased studies of tuberculin after reports of severe reactions to one who persisted after his initial patients died of a severe form of malaria in 1918 and then to one who after 1928 considered a treatment which still had a mortality of up to 20 percent for psychiatric illnesses. There was also an emergence from the young man who had married a Jewish woman to an older one who became more and more vocal about his views on "racial hygiene."2

Wagner-Jauregg had also practiced sterilization as a possible treatment for psychoses in the 1920s, which may have been a forerunner to his now strong voice for the forced sterilization of persons he considered less well-endowed genetically. The practical applications of such thinking contributed to the horrors of the Third Reich, and later his reputation died along with it.

The next post explores the intriguing question of how he and Freud, who shared many similarities in background, remained friends for decades until the tumultuous 1930s and how their personalities and experiences led them to take such very different trajectories.

Portions of this article are adapted from The Psychoanalyst and the Nazi Nobelist: The Curious Story of Sigmund Freud and Julius Wagner-Jauregg.

References

1. Henry, G.W. (1941). Organic mental diseases. In: A history of medical psychology. (Zilbourg, G.W., ed.), New York, W.W. Norton, pp. 526-559.

2. Gartlehner, G. and Stepper, K.: Julius Wagner-Jauregg: pyrothrapy, simultanmethode, and ‘racial hygiene’. J. Royal Soc. Med. 105: 357-259, 2012.