Bipolar Disorder

Herman Melville and the Question of Bipolar Disorder

Part III of a series examining Melville’s life and struggle with mental illness.

Posted November 23, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- The most common interpretation of Herman Melville's troubled life is that he experienced a form of bipolar disorder.

- If there is an association of bipolar disorder with creativity, its frequency compared to the rarity of great art suggests other factors at work.

- Creativity may be enhanced when symptoms of bipolar disorder ally with personality traits and the milieu of the times.

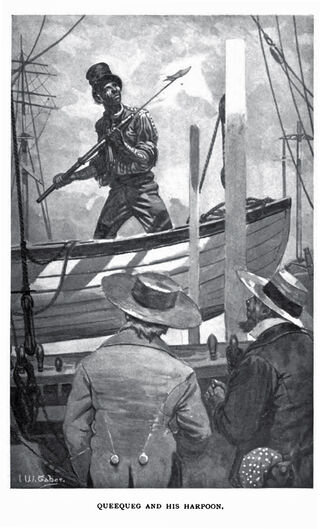

In Part I and Part II of this series, I described Herman Melville’s life, including his early years as a sailor in the South Pacific, his growing fame as a writer of adventure tales, his friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne, the writing of Moby-Dick, his attempts to recapture his fame by moving into poetry and religious themes, and his later years of isolation and decline. In it, I touched upon both his periods of depression as well as times of great productivity in which he was remarkably energetic, often euphoric, and grandiose. In this final installment, we will look at how his experience has been viewed in terms of mental illness.

Melville's family history

Melville’s afflictions have been interpreted many different ways, but the most common view has been that he suffered from bipolar disorder (1,2). His family history has been taken to support this. His father, a man of seemingly limitless energy, kept moving the family into larger and larger houses which he could ill afford, as part of a grandiose and exuberant manner evident in most of his dealings. In December 1831, he became ill after returning to Albany from New York, where he had been dealing with the debts incurred from unwise business ventures, and riding in an open carriage for two days. It has been suggested that he died ‘‘manic, insane, and bankrupt’’ (2). An alternative view, however, is that the extreme agitation and seemingly manic behavior in the weeks before his death may have resulted from delirium. A similar argument applies to his brother Gansevoort, who has been described as "mad" in the month before his death at age 30 (3) but showed little evidence of manic behavior during most of his life, until his last weeks when fatal tuberculosis may have caused meningitis.

Clearer evidence for depression is evident in Melville’s mother and maternal grandmother and maternal uncle. A maternal aunt resided in an asylum, and his cousin Henry was ruled insane. Melville seemed to recognize the significance of this burden, as in passages in Moby-Dick referring to "the genealogies of these high mortal miseries" (1,4). His son Malcolm later committed suicide in 1867 at age 18 in the midst of father-son disagreements, in a sense bringing home a family history in the most personal of ways.

Melville's writing process

Turning to Melville’s own history, it is clear that he had periods of intense activity, writing, for instance, the two novels Redburn and White-Jacket in only four months. Moby-Dick was written in what has sometimes been described as almost a frenzy of activity, with extremely long hours and little pause for food or rest. In the period before revising it, he described Hawthorne in the most grandiose of terms; he referred to himself in a lofty manner ("Give me Vesuvius’ crater for an inkstand!") and at other times, perhaps humorously, said he needed at least 50 assistants to keep track of all his future projects.

His writing itself has sometimes been interpreted as "a scattergun spray of images" approaching "flight of ideas," and it has been speculated that such passages were written in a manic or hypomanic state, then edited later when euthymic or mildly depressed (1). At other times, he was profoundly depressed, which he likened to when a Catskill eagle descends into the "blackest gorges."

In the years following Moby-Dick, his mood swings were much more in this direction. He sought solace in travel to Europe and the Holy Land, and later on a sea voyage around Cape Horn on his brother’s ship, without relief. For much of the remainder of his life, he appeared depressed and irritable, a tyrant at home. His last years were spent as a dispirited recluse, though some have interpreted parts of Billy Budd to suggest a reconciliation with life.

What bipolar illness could mean about Melville's work

We will never really know whether Melville had bipolar illness in the absence of a careful in-person psychiatric evaluation. If he did, as many believe, the question remains as to what that means.

There is a long tradition suggesting a higher rate of bipolar illness in creative people. Kay Jamison’s often-cited study found that 38 percent of a group of British writers and artists had sought help for a mood disorder (5), but this also suggests that 62 percent had not. Artists and writers as a group have not always scored higher on measures of bipolar symptoms (6), and bipolar patients do not necessarily show more creativity than other patients (7).

There is also the disparity between the very high frequency of bipolar illness, which is experienced by 4.4 percent of Americans in their lifetimes, and the very rare occurrence of brilliant writers. If bipolar illness were to contribute to creativity, it seems more likely that it would do so when in combination with other traits, which speculatively might include curiosity, commitment, fluency, discipline, and other still-elusive factors. A too-close focus on illness alone can also overlook the interaction with the milieu of the times, which for Melville included the economic importance (and later decline) of whaling and the devastation wrought by the Civil War.

Nonetheless, one is left with a sense that if Melville did experience bipolar disorder, there may have been a very intimate relationship between the illness and his work. It could be that depression led to his vivid descriptions of the darker parts of the human condition and how to understand evil, while hypomanic states fueled both his imagination and the energy for such prodigious and rapid output. Some have gone so far as to wonder whether, if modern treatments for mood disorders had been available, his greatest works would ever have been written.

Portions of this post are adapted from Fragile Brilliance: The Troubled Lives of Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, and Other Great Authors.

References

1. Dolman, C. and Turvey, S.: The impact of Melville’s manic-depression on the writing of Moby Dick. Mental Health Review Journal 16: 107-112, 2011.

2. Jamison, K.: Touched with fire. Manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. Simon&Schuster, New York, 1994.

3. Miller, E.: Melville. George Braziller, New York, 1975.

4. Melville, H.: Moby Dick, or the Whale. Penguin Classics, New York, 1992 edition.

5. Jamison, K.R.: Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry 52: 125, 1989.

6. Pavrita, K.S. et al.: Creativity and mental health: a profile of writers and musicians. Indian J. Psychiat. 49: 34-43, 2007.

7. Ghadarian, A.-M. et al.: Creativity and the evolution of psychopathologies. Creativity Res. J.: 13: 145-148, 2000-2001.